Price Discrimination

- What is price discrimination?

- Third degree price discrimination

- First degree (or perfect) price discrimination

- Second degree price discrimination

What is price discrimination?

Price discrimination happens when a firm charges different prices to different customers, usually based on some verifiable characteristic.

A common example of price discrimination is student and veteran discounts. If a consumer can prove that they are a student or a veteran, the firm is willing to charge them a lower price.

Another example of price discrimination is through the use of coupons. The differentiating characteristic is whether the consumer is willing to spend the time to look for coupons.

Usually, the discounts are targeted at consumer groups with more elastic demand. In other words, the discounts are targeted at more price-sensitive groups, while the less price-sensitive groups pay full price.

Warning

It’s only price discrimination if the product being sold at different prices is the same. Thus, charging more money for a business class seat is not price discrimination, because the business class seat and the economy class seat are not the same product. Similarly, charging a higher auto insurance premium to a risky driver is not price discrimination because it costs the insurance company more to insure risky drivers than safe drivers.

Third degree price discrimination

Third degree price discrimination happens when a firm can identify (and verify) at least two groups of consumers. It then charges a different price to each group. This usually results in higher profit than if it charged a single price to all consumers.

Example 1

A commodity \(q\) is supplied by a monopolist with total cost function:

\[c(Q) = Q\]There are two representative consumers. Representative consumer 1 has income \(Y_1 = 500\) and utility function:

\[u_1(c_1, q_1) = c_1 + 25q_1 - \frac{1}{2} q_1^2\]Representative consumer 2 has income \(Y_2 = 400\) and utility function:

\[u_2(c_2,q_2) = c_2 + 13q_2 - \frac{1}{2} q_2^2\]If the firm can price discriminate, find the price it would charge to each consumer and calculate the total profit.

Answer.

Step 1: Solve consumer 1’s problem to derive their demand curve.

\[\max_{q_1} ~ 500 - p_1 q_1 + 25q_1 - \frac{1}{2} q_1^2\]The first order condition is:

\[p_1 = 25 - q_1\]Step 2: Solve consumer 2’s problem to derive their demand curve:

\[\max_{q_2} ~ 400 - p_2 q_2 + 13q_2 - \frac{1}{2} q_2^2\]The first order condition is:

\[p_2 = 13 - q_2\]Step 3: Write down the firm’s optimization problem.

\[\begin{align} & ~ \max_{p_1, q_1, p_2, q_2} ~ p_1 q_1 + p_2 q_2 - (q_1 + q_2) ~ \text{s.t.} ~ p_1 = 25 - q_1 ~ \text{and} ~ p_2 = 13 - q_2 \\ = & ~ \max_{q_1, q_2} ~ (25 - q_1) q_1 + (13 - q_2) q_2 - q_1 - q_2 \\ = & ~ \max_{q_1, q_2} ~ 24q_1 - q_1^2 + 12q_2 - q_2^2 \end{align}\]Step 4: This now has the form of an unconstrained multivariate optimization problem, so simply write down the first order conditions and solve them:

\[\begin{align} \text{FOC}[q_1]: ~ 24 - 2q_1 &= 0 \\ q_1 &= 12 \end{align}\] \[\begin{align} \text{FOC}[q_2]: ~ 12 - 2q_2 &= 0 \\ q_2 &= 6 \end{align}\]Step 5: Plug \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) into the consumers’ demand curves to get \(p_1\) and \(p_2\).

\[\begin{align} p_1 &= 25 - q_1 = 13 \\ p_2 &= 13 - q_2 = 7 \end{align}\]Step 6: Plug \(p_1\), \(q_1\), \(p_2\), \(q_2\), into the profit function to get profit.

\[\begin{align} \Pi &= p_1 q_1 + p_2 q_2 - (q_1 + q_2) \\ &= (13)(12) + (7)(6) - (12+6) \\ &= 180 \end{align}\]

Example 2

Take the setup from Example 1. Suppose the firm was not able to price discriminate. What price would it charge to both consumers? Calculate the firm’s profit.

Answer.

Step 1: Write down the market demand curve.

We know from Example 1 that \(q_1 = 25 - p\) and \(q_2 = 13 - p\). We can combine the two demand curves to get:

\[\begin{align} Q &= q_1 + q_2 \\ &= (25 - p) + (13 - p) \\ &= 38 - 2p \end{align}\]Step 2: Rewrite the demand curve as an “inverse demand curve”. (Note: An inverse demand curve simply takes the demand curve and write it as price equals a function of quantity.)

\[\begin{align} Q &= 38 - 2p \\ 2p &= 38 - Q \\ p &= 19 - \frac{1}{2}Q \end{align}\]Step 3: Write the firm’s problem as if it faces a single market demand curve and is just choosing a single price and quantity.

\[\begin{align} & ~ \max_{p,Q} ~ pQ - Q ~ \text{s.t.} ~ p = 19 - \frac{1}{2}Q \\ = & ~ \max_{Q} ~ (19 - \frac{1}{2}Q)Q - Q \\ = & ~ \max_{Q} ~ 18Q - \frac{1}{2}Q^2 \end{align}\]Step 4: Solve the first order condition.

\[\begin{align} \text{FOC}[Q]: 18 - Q &= 0 \\ Q &= 18 \end{align}\]Step 5: Plug \(Q\) into the inverse demand curve to get \(p\).

\[p = 19 - \frac{1}{2}Q = 19 - \frac{1}{2} (18) = 10\]Step 6: Plug \(Q\) and \(p\) into the profit function to get profit.

\[\Pi = pQ - Q = 10(18) - 18 = 162\]

First degree (or perfect) price discrimination

First degree price discrimination (also called perfect price discrimination) happens when the firm knows perfectly the demand curve of each individual consumer. It can also verify the identity of each consumer and charge different prices to each consumer.

A firm is then able to charge each consumer exactly what they are willing to pay for the product, no less. By doing this, the firm extracts all of the surplus available in the market.

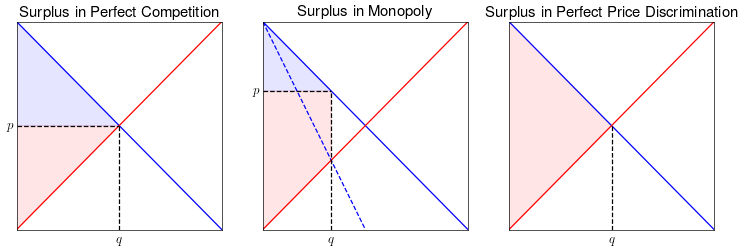

The diagram below illustrates the distribution of surplus in a market with perfect price discrimination. The market is efficient because all of the available surplus is extracted, but it is highly inequitable as the firm accumulates all of the surplus available in the market.

(The red shaded region shows producer surplus and the blue shaded region shows consumer surplus.)

Second degree price discrimination

Second degree price discrimination happens when the firm can’t perfectly identify all individuals, but it does know their demand curves.

What the firm can do is charge a fixed entry fee that extracts all of the surplus of at least one of the consumer groups. It then charges a price on top of the fixed entry fee. This is sometimes known as club pricing or two-part tariffs, because the price comes in two parts: an entry fee and a unit price.

We won’t solve second degree price discrimination problems in this class. But you can reference the Nicholson and Snyder textbook if you want to learn more.