Theory of Production

In this lecture, we’ll survey some ideas from the theory of production. The purpose of this theory is to understand how firms make production decisions. This includes the decision of how many of each input factor to employ (i.e. labor and capital) and how much output to produce. The ideas from this lecture are often used in macroeconomic models that try to explain factor prices like wages and interest rates.

General Setup

A firm has a production process that uses labor and capital. Labor refers to human effort, whereas capital refers to things like equipment, machines, land, and software. If the firm employs \(L\) units of labor and \(K\) units of capital, it produces \(Y\) units of commodity output. The relationship between output \(Y\) and inputs \(L\) and \(K\) is given the production function, \(f(L,K)\):

\[Y = f(L,K)\]The firm is a price taker in both the commodity market and the factor markets. It can sell its output commodity at unit price \(p\), it employs labor at unit wage rate \(w\), and it employs capital at unit price \(r\).

The firm’s optimization problem is therefore:

\[\max_{L,K} ~ pf(L,K) - wL - rK\]That is, the firm chooses how much labor \(L\) and capital \(K\) to employ in order to maximize its profits.

Returns to Scale

An important aspect of the production function is its returns to scale. “Returns to scale” asks the question: if all inputs are scaled up or down by an equal factor, how does that affect the commodity output?

- If scaling all inputs up or down by \(X\%\) results in a \(X\%\) change in output, then we say that the production function has constant returns to scale.

- If scaling all inputs up or down by \(X\%\) results in a smaller than \(X\%\) change in output, then we say that the production function has decreasing returns to scale.

- If scaling all inputs up or down by \(X\%\) results in a larger than \(X\%\) change in output, then we say that the production function has increasing returns to scale.

Example

A firm increases its labor and capital inputs by 10%. Its output increases by 8%. Does the firm has constant, increasing, or decreasing returns to scale?

Answer. Decreasing returns to scale.

Example

A firm decreases its labor and capital inputs by 5%. Its output decreases by 10%. Does the firm has constant, increasing, or decreasing returns to scale?

Answer. Increasing returns to scale.

Example

A firm increases its labor and capital inputs by 7%. Its output increases by 7%. Does the firm has constant, increasing, or decreasing returns to scale?

Answer. Constant returns to scale.

Example

A firm increases its labor input by 8% and its capital input by 3%. Its output increases by 5%. Does the firm has constant, increasing, or decreasing returns to scale?

Answer. Unknown. The definition of returns to scale only applies when both inputs are scaled up or down by equal amounts.

Cobb Douglas Production Functions

A commonly used model of the production function is the Cobb Douglas production function. A Cobb Douglas production function has the following form:

\[f(L,K) = AL^{a} K^{b}\]The Cobb Douglas production function is governed by three parameters, \(A\), \(a\), and \(b\):

- \(A\), called the total factor productivity, controls how productive the firm is overall.

- \(a\) controls the relative importance of labor in the production process.

- \(b\) controls the relative importance of capital in the production process.

An interesting feature of the Cobb Douglas production function is that you can tell whether it has constant, increasing, or decreasing returns to scale simply by looking at \(a\) and \(b\).

- If \(a + b = 1\), then the Cobb Douglas production function has constant returns to scale.

- If \(a + b < 1\), then the Cobb Douglas production function has decreasing returns to scale.

- If \(a + b > 1\), then the Cobb Douglas production function has increasing returns to scale.

Proof

Suppose both \(K\) and \(L\) are scaled by a factor of \(\alpha>1\).

\[\begin{align} f(\alpha L, \alpha K) &= A(\alpha L)^{a} (\alpha K)^{b} \\ &= A \alpha^a L^a \alpha^b K^b \\ &= \alpha^{a+b} A L^a K^b \\ &= \alpha^{a+b} f(L, K) \end{align}\]

- If \(a+b=1\), then \(f(\alpha L, \alpha K) = \alpha f(L, K)\). That is, the production is scaled by exactly \(\alpha\), so the firm has constant returns to scale.

- If \(a+b<1\), then \(f(\alpha L, \alpha K) < \alpha f(L, K)\), so production is scaled by less than \(\alpha\), and the firm has decreasing returns to scale.

- If \(a+b>1\), then \(f(\alpha L, \alpha K) > \alpha f(L, K)\), so production is scaled by more than \(\alpha\), and the firm has increasing returns to scale.

Example

A firm uses labor \(L\) and capital \(K\) to produce a commodity output. The production function is:

\[f(L, K) = L^{1/2} K^{1/4}\]

- Does the firm exhibit increasing, decreasing, or constant returns to scale?

- Suppose the firm reduces both its labor and capital input by 50%. This would cause the firm’s output to decrease by a factor of what?

- Suppose the firm reduces is labor input by 50% without changing its capital input. This would cause the firm’s output to decrease by a factor of what?

Answer.

\(a=1/2\) and \(b=1/4\), so \(a+b = 3/4\). The firm exhibits decreasing returns to scale.

- \[\begin{align} f( 0.5 L, 0.5 K) &= (0.5 L)^{1/2} (0.5 K)^{1/4} \\ &= (0.5)^{1/2} L^{1/2} (0.5)^{1/4} K^{1/4} \\ &= (0.5)^{3/4} L^{1/2} K^{1/4} \\ &= (0.5)^{3/4} f(L, K) \\ &= 0.595 f(L, K) \end{align}\]

A 50% reduction in both labor and capital reduces output by 40.5%.

- \[\begin{align} f( 0.5L, K) &= (0.5 L)^{1/2} K^{1/4} \\ &= (0.5)^{1/2} L^{1/2} K^{1/4} \\ &= (0.5)^{1/2} f(L, K) \\ &= 0.707 f(L, K) \end{align}\]

A 50% reduction in labor without a change in capital reduces output by 29.3%.

Cost Minimization

A useful, alternative formulation to the profit maximization problem is the cost minimization problem. The cost minimization problem is especially useful when analyzing firms that have constant returns to scale. The idea behind cost minimization is to ask: what is the minimum cost for me to produce 1 unit of output?

The cost minimization problem is written as follows:

\[\min_{L, K} ~ wL + rK ~ \text{ s.t. } ~ f(L,K) = 1\]That is, choose \(L\) and \(K\) to minimize cost, such that the total amount of output is 1 unit.

First order conditions

This is a standard contrained multivariate optimization problem. The first order conditions are:

\[\begin{align} w &= \lambda f_L(L, K) \\ r &= \lambda f_K(L, K) \end{align}\]The two first order conditions and the constraint \(f(L,K)=1\) gives us three equations in three unknowns: \(L\), \(K\), and \(\lambda\). The system can thus be solved for the optimal combination of labor and capital to use to produce one unit of output, as well as the cost to produce one unit.

The two first order conditions also give us some economic insight: when firms are behaving optimally, the wage rate will be proportional to the marginal product of labor (\(f_L(L,K)\)), and the price of capital will be proportional to the marginal product of capital (\(f_K(L,K)\)).

Economic Insight

When firms are behaving optimally, the wage rate will be proportional to the marginal product of labor and the price of capital will be proportional to the marginal product of capital.

Example

A firm has a constant returns to scale production function over labor and capital given by:

\[f(L, K) = \frac{1}{4} L^{3/4} K^{1/4}\]The unit price of labor is \(w=5\) and the unit price of capital is \(r=4\).

- What choice of labor minimizes the cost to produce one unit of output?

- What choice of capital minimizes the cost to produce one unit of output?

- What is the firm’s cost to produce one unit?

Answer.

Step 1. Write down the cost minimization problem.

\[\min_{L, K} ~ 5L + 4K ~ \text{ s.t. } ~ \frac{1}{4} L^{3/4} K^{1/4} = 1\]Step 2. Write down the first order conditions.

\[\begin{align} 5 &= \frac{3}{16} \lambda L^{-1/4} K^{1/4} \\ 4 &= \frac{1}{16} \lambda L^{3/4} K^{-3/4} \end{align}\]Step 3. Divide the two first order conditions and simplify.

\[\begin{align} \frac{5}{4} &= \frac{3 L^{-1/4} K^{1/4}}{L^{3/4} K^{-3/4}} \\ \frac{5}{4} &= \frac{3 K}{L} \\ L &= \frac{12}{5} K \end{align}\]Step 4. Plug \(L = \frac{12}{5}K\) into the constraint and solve for \(K\).

\[\begin{align} \frac{1}{4} L^{3/4} K^{1/4} &= 1 \\ \frac{1}{4} \left( \frac{12}{5} K \right)^{3/4} K^{1/4} &= 1 \\ \frac{1}{4} \left( \frac{12}{5} \right)^{3/4} K^{3/4} K^{1/4} &= 1 \\ \frac{1}{4} \left( \frac{12}{5} \right)^{3/4} K &= 1 \\ 0.4821 K &= 1 \\ K &= 2.0744 \end{align}\]Step 5. Plug \(K=2.0744\) into \(L = \frac{12}{5}K\) to get \(L\).

\[L = 4.9787\]Step 6. Plug \(L\) and \(K\) into the \(5L + 4K\) to get the cost to produce 1 unit.

\[MC = 5 \times 4.9787 + 4 \times 2.0744 = 33.191\]

Graphical representation of cost minimization

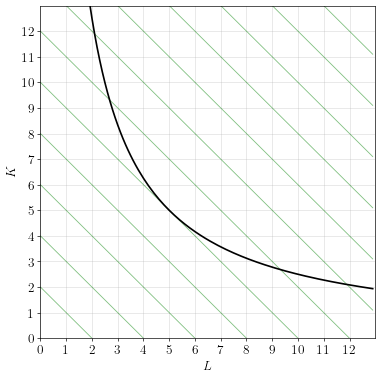

Cost minimization can be represented graphically by an isoquant and isocost curves, as illustrated below.

The curved black line is called an isoquant. It represents the combinations of \(L\) and \(K\) that can be combined to produce one unit of output. It is our constraint in the cost minimization problem.

The straight green lines are called isocost curves. Think of these as contour lines representing a hill, and the hill is the total cost for employing different combinations of labor and capital. The hill is rising in the northeast direction, but our goal is to minimize costs, not to maximize them.

The choice of \(L\) and \(K\) that minimizes costs is the lowest point on the hill that’s touching the constraint. That occurs when the isocost curves are tangent to the isoquant: \(L=5\) and \(K=5\).

Example

A firm has a constant returns to scale production function. Its unit isoquant and isocost curves are shown in the diagram below.

The unit price of labor is \(w=5\) and the unit price of capital is \(r=2\).

- What choice of \(L\) and \(K\) minimize the cost to produce one unit?

- What is the cost to produce one unit of output?

Answer.

The cost to produce one unit is minimized when \(L=3\), \(K=7\). The cost to produce one unit is \(5 \times 3 + 2 \times 7 = 29\).