Application: In-Kind vs. Monetary Transfers

In-kind vs. monetary transfers

A food stamp is a voucher that the government gives to low-income households to help them buy food. Food stamps can only be used on food. Have you ever wondered if low-income households would be better off if the government just gave them money instead?

Note

A direct transfer of a commodity is called an in-kind transfer. A transfer of money is called a monetary transfer. Food stamps are a type of in-kind transfer since they can only be used to buy food.

The two examples below will use graphical analysis and consumer choice theory to show that monetary transfers are always preferable in-kind transfers.

Example where monetary transfers are preferable to in-kind

Example

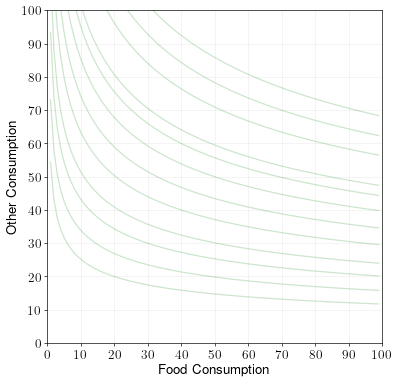

A consumer gets utility from food consumption \(x\) and “other consumption” \(y\). The consumer has income \(I=60\). The price of both food is \(p_x=1\) and the price of other goods is also \(p_y=1\). The consumer’s utility function is shown by the following indifference curves:

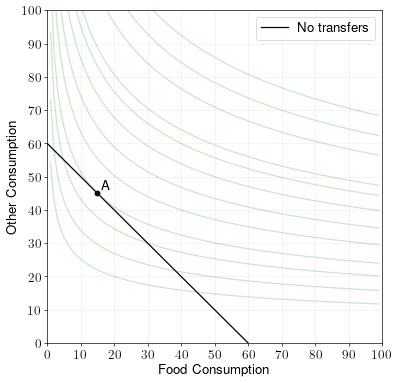

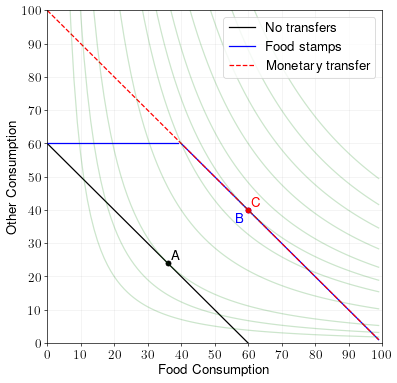

Draw the budget line and mark the optimal point. Label it “A”.

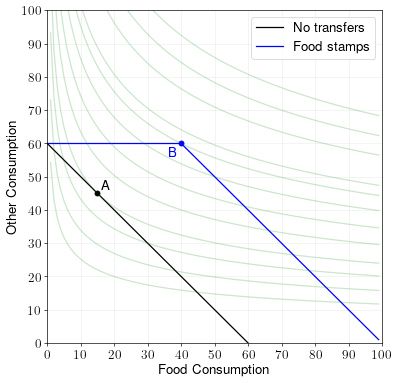

Suppose the consumer receives food stamps worth 40 units of food without spending any of his own money. Draw the new budget line and find the new optimal point. Label it “B”.

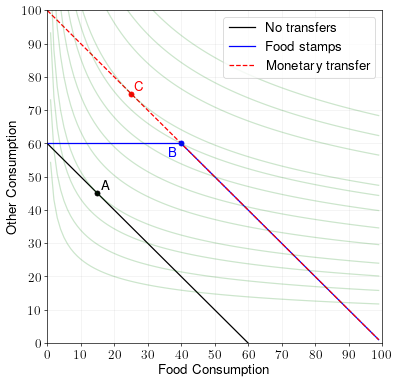

Now suppose that the consumer instead receives a direct monetary transfer of 40 dollars. Draw the new budget line and find the new optimal point. Label it “C”. Is the utility at “C” higher or lower than the utility at “B”?

Answer to part 1.

The x and y intercepts of the budget line are both \(60\). The optimal point is on the indifference curve tangent to the budget line.

Answer to part 2.

The budget line shifts right by 40 units. That’s because the consumer can now spend all 60 dollars of his income on \(y\) and still receive 40 units of \(x\). He can buy more \(x\) if he wants, but he cannot consume more \(y\) than his base income allows.

Answer to part 3.

The budget line now extends backwards because it’s as if the consumer has 100 dollars of income instead of 60 dollars. “C” lines on an indifference curve that is northeast of “B”, so it has higher utility.

Example where monetary transfers are equivalent to in-kind

Example

A consumer gets utility from food consumption \(x\) and “other consumption” \(y\). The consumer has income \(I=60\). The price of both food is \(p_x=1\) and the price of other goods is also \(p_y=1\). The consumer’s utility function is shown by the following indifference curves:

Draw the budget line and mark the optimal point. Label it “A”.

Suppose the consumer receives food stamps worth 40 units of food without spending any of his own money. Draw the new budget line and find the new optimal point. Label it “B”.

Now suppose that the consumer instead receives a direct monetary transfer of 40 dollars. Draw the new budget line and find the new optimal point. Label it “C”. Is the utility at “C” higher or lower than the utility at “B”?

Answer to all parts.

Following the same logic as the previous example, we get the diagram below. “B” and “C” give the same utility, so the monetary transfer is not strictly preferable to the food stamps in this example. However, neither are the food stamps strictly preferable to the monetary transfer.

In-kind transfers are never preferable to monetary

Since the effect of a monetary transfer is simply to extend the budget line, there is no scenario (under our current framework) where in-kind transfers are preferable.

Economic Insight

If consumers are rational, then in-kind transfers will never result in higher consumer utility than monetary transfers of the same value.

Therefore, in-kind transfers need to be justified by arguments outside the framework of rational utility maximization. Either consumers are not rational (i.e. they don’t know what’s best for themselves), or public policy has objectives beyond maximizing consumers’ hedonic utility (for example, the government may want to promote healthy eating even if it’s not the consumer’s first preference.)