Theory of Consumer Choice

- General setup

- First order conditions

- Marginal rate of substitution

- MRS and prices

- Graphical representation

General setup

A consumer has income \(I\) and chooses how much of a good \(x\) and how much of a good \(y\) to consume.

The price of good \(x\) is \(p_x\) and the price of good \(y\) is \(p_y\). The consumer takes prices as given.

If the consumer purchases \(x\) units of good \(x\), and \(y\) units of good \(y\), he gets utility \(u(x,y)\).

The consumer’s optimization problem is:

\[\max_{x,y} ~ u(x,y) ~ \text{ s.t. } p_x x + p_y y = I\]We call \(u(x,y)\) the consumer’s utility function. It maps consumption onto a measure of the consumer’s total pleasure from consuming these goods. “Pleasure” is defined broadly, and it is assumed that consumers always try to maximize their utility.

We call the constraint, \(p_x x + p_y y = I\) the budget constraint. It basically says that the consumer can’t spend more than his income. (We also assume they spend all their income–we’ll deal with the possibility of borrowing and savings later.)

The consumer’s optimization problem is therefore to maximize their utility subject to their budget constraint.

First order conditions

This is a constrained multivariate optimization problem, which we can solve using the methods described in the previous chapters.

The first order conditions are:

\[\begin{align} u_x(x,y) &= \lambda p_x \\ u_y(x,y) &= \lambda p_y \end{align}\]This gives us three equations in three unknowns. The three unknowns are \(x\), \(y\), and \(\lambda\). The three equations are the two first order conditions and the budget constraint.

Example 1

A consumer with income \(I = 50\) has a utility function over two goods, \(x\) and \(y\), given by:

\[u(x,y) = x^{\frac{1}{2}} y^{\frac{1}{2}}\]The price of good \(x\) is \(p_x = 2\) and the price of good \(y\) is \(p_y = 1\).

Calculate the consumer’s optimal choice of \(x\) and \(y\).

Answer.

Step 1. Write down the optimization problem.

\[\begin{align} \max_{x,y} ~ x^{\frac{1}{2}} y^{\frac{1}{2}} ~ \text{ s.t. } ~ 2x + y = 50 \end{align}\]Step 2. Write down the first order conditions:

\[\begin{align} \frac{1}{2} x^{-\frac{1}{2}} y^{\frac{1}{2}} &= 2 \lambda \\ \frac{1}{2} x^{\frac{1}{2}} y^{-\frac{1}{2}} &= 1 \lambda \end{align}\]Step 3. Divide the two first order conditions:

\[\begin{align} \frac{\frac{1}{2} x^{-\frac{1}{2}} y^{\frac{1}{2}}}{\frac{1}{2} x^{\frac{1}{2}} y^{-\frac{1}{2}}} &= 2 \\ \frac{y}{x} &= 2 \\ y &= 2x \end{align}\]Step 4. Plug \(y=2x\) into the budget constraint.

\[\begin{align} 2x + y &= 50 \\ 2x + (2x) &= 50 \\ 4x &= 50 \\ x &= 12.5 \end{align}\]Step 5. Plug \(x=12.5\) into the budget constraint to solve for \(y\).

\[\begin{align} 2x + y &= 50 \\ 2(12.5) + y &= 50 \\ 25 + y &= 50 \\ y &= 25 \end{align}\]So the consumer’s optimal choice is \(x=12.5\) and \(y=25\).

Marginal rate of substitution

If we divide the two first order condition equations by each other, we get:

\[\begin{align} \frac{u_x(x,y)}{u_y(x,y)} &= \frac{p_x}{p_y} \end{align}\]This says that at the optimal choice, the ratio of marginal utility of good \(x\) to the marginal utility of good \(y\) is equal to the ratio of prices.

We call the ratio of marginal utility between two goods the marginal rate of substitution between the two goods (or MRS).

It’s called marginal rate of substitution because it’s the ratio of trade that would keep the consumer’s utility constant. Thus, consumers are willing to substitute between these two goods at the marginal rate of substitution.

Definition

We call the ratio of marginal utility between two goods the marginal rate of substitution between the two goods.

If the MRS between good \(x\) and good \(y\) is \(2.5\), this means that the consumers gets \(2.5\) utility from \(x\) for every \(1\) utility they get from \(y\). (In other words, they value good \(x\) at \(2.5\) times the rate at which they value good \(y\).) It also means they’re willing to give up \(2.5\) units of \(y\) in order to get \(1\) unit of \(x\).

Example 2

A consumer’s marginal rate of substitution between coffee and tea is \(1.5\). How much tea is the consumer willing to give up to get one unit of coffee? How much coffee is the consumer willing to give up to get one unit of tea?

Answer.

The consumer is willing to give up \(1.5\) units of tea to get one unit of coffee.

The consumer is willing to give up \(1/1.5 = 0.667\) units of coffee to get one unit of tea.

Example 3

A consumer’s utility function between good \(x\) and good \(y\) is:

\[u(x,y) = x^{\frac{1}{3}} y^{\frac{2}{3}}\]Write down the consumer’s MRS between good \(x\) and good \(y\), expressed in terms of \(x\) and \(y\). Calculate the MRS when \(x=2\) and \(y=3\). Describe how the MRS changes as \(x\) and \(y\) change.

Answer.

The MRS between \(x\) and \(y\) is defined as:

\[\frac{u_x (x,y)}{u_y(x,y)}\]The partial derivative of \(u(x,y)\) with respect to \(x\) is:

\[u_x (x,y) = \frac{1}{3} x^{-\frac{2}{3}} y^{\frac{2}{3}}\]The partial derivative of \(u(x,y)\) with respect to \(y\) is:

\[u_y (x,y) = \frac{2}{3} x^{\frac{1}{3}} y^{-\frac{1}{3}}\]The MRS between \(x\) and \(y\) is therefore:

\[\begin{align} \frac{u_x(x,y)}{u_y(x,y)} &= \frac{\frac{1}{3} x^{-\frac{2}{3}} y^{\frac{2}{3}}}{\frac{2}{3} x^{\frac{1}{3}} y^{-\frac{1}{3}}} \\ &= \frac{y}{2x} \end{align}\]When \(x=2\) and \(y=3\), the MRS is \(3/4\).

The MRS increases when \(y\) increases and decreases when \(x\) increases.

This means that \(x\) becomes relative more valuable when the consumer’s consumption of \(y\) increases. Conversely, \(x\) becomes relatively less valuable when the consumer’s consumption of \(x\) increases.

This utility function exhibits diminishing marginal rate of substitution. That is, the marginal rate of substitution between \(x\) and \(y\) decreases as consumption of \(x\) increases. Diminishing marginal rate of substitution is a fancy way of saying that people have a taste for variety.

Economic Insight

Most utility function will exhibit diminishing marginal rate of substitution. This means that the MRS between \(x\) and \(y\) decreases when consumption of \(x\) increases. Diminishing MRS comes from consumers’ taste for variety.

MRS and prices

The first order conditions show that at the consumer’s optimal choice, the marginal rate of substitution between two goods is equal to the ratio of the price between the two goods.

This makes sense: if the MRS between goods \(x\) and \(y\) is \(2.5\), it means that the consumer values \(x\) by \(2.5\) times more than \(y\). It also means that they’re willing to pay \(2.5\) times more for good \(x\) than for good \(y\). If the ratio of prices is less than \(2.5\), the consumer should buy more of \(x\). If the ratio of prices is more than \(2.5\), the consumer should buy less of \(x\). Optimality is achieved when ratio of prices equals the MRS.

Economic Insight

At a consumer’s optimal choice, the marginal rate of substitution between two goods equals the ratio of the price between the two goods.

Example 4

The price of bananas is $1.25 per bundle. The price of apples is $0.70 per unit. Consumers will purchase bananas and apples until their marginal rate of substitution between bananas and apples is?

Answer. They’ll consume bananas and apples until the MRS between bananas and apples is \(1.25 / 0.70 = 1.79\).

Graphical representation

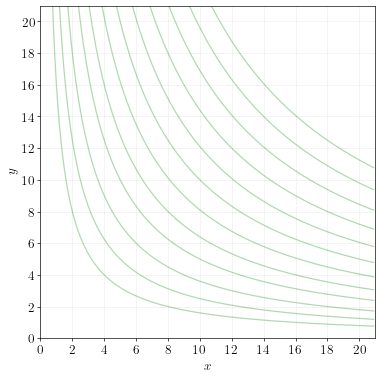

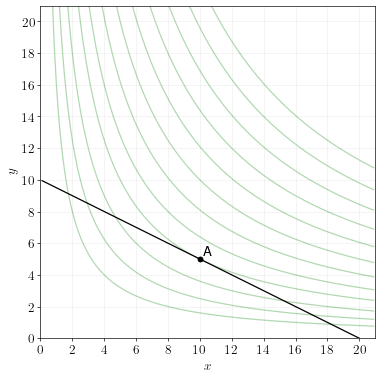

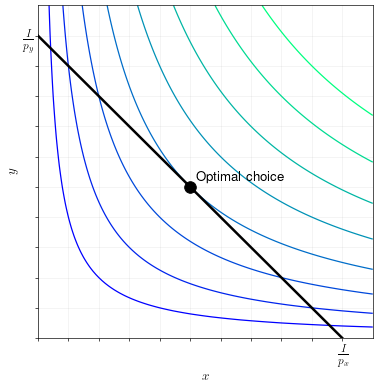

The general consumer choice problem can be represented graphically as follows:

The budget constraint will always be a straight line. The \(y\) intercept of the budget line is \(\frac{I}{p_y}\) (spend all the income \(y\)). The \(x\) intercept of the budget line is \(\frac{I}{p_x}\) (spend all income on \(x\)). The slope of the budget line is always \(-\frac{p_x}{p_y}\).

The curves show the contour lines for the utility function. We also call these indifference curves. Utility is always increasing in the northeast direction (more \(x\) and more \(y\) is better.)

At any point \((x,y)\), the slope of the indifference curve at that point is: \(- \frac{u_x(x,y)}{u_y(x,y)}\).

In other words, the slope of the indifference curves are equal the marginal rate of substitution between \(x\) and \(y\).

At the utility maximizing point, the budget line is just tangent to an indifference curve. Since the slope of the budget line is the ratio of \(p_x\) to \(p_y\), and the slope of the indifference curve is MRS, we see once again that utility is optimized when MRS equals the ratio of the prices.

Tip

To draw the graphical representation of consumer choice between two goods, make use of the following tidbits:

The slope of the budget line is always equal to \(- \frac{p_x}{p_y}\).

The y-intercept of the budget line is always \(\frac{I}{p_y}\).

The x-intercept of the budget line is always \(\frac{I}{p_x}\).

The utility-maximizing choice of \(x\) and \(y\) occurs on the indifference curve that is just tangent to (just touching) the budget line.

Example 5

A consumer with income \(I=100\) derives utility from two goods, \(x\) and \(y\). The price of \(x\) is \(p_x=5\) and the price of \(y\) is \(p_y=10\).

The consumer’s utility function is represented by the indifference curves shown in the diagram below.

Draw the budget line and find the optimal consumption of \(x\) and \(y\).

Answer.

To x-intercept of the budget line is \(I/p_x = 100/5 = 20\). The y-intercept of the budget line is \(I/p_y = 100/10 = 10\). The optimal point occurs on the indifference curve that just touches the budget line, which is marked by point “A” on the diagram below. The optimal consumption is \(x=10\) and \(y=5\).